Month: September 2019

Mirimari

Borya

The Chronicles of Narva

One.

Long, straight avenues named Pushkin. Geometry, but not like home – a more authoritarian rigidity, a purity imposed from above, exceeding in its ambition even the neo-Calvinist adherents of Mondriaan. A fractal replication of ideal shapes, although the execution is jagged.

It is the idea that matters here, not the façade. It is the inverse of home, where an ascendant pragmatism, expressed in an elegant harmony of contours, provides spatial cover for my nation’s fearful suspicion of philosophies and violent passions. Communist urban planning is Platonic. Ours can’t be linked to a name; it is simply petit-bourgeois. To my mother country, I must be an ungrateful, ambivalent son.

We walk from the residency to a Lutheran church. A purple-nosed priest welcomes us and narrates the indignities the building has suffered over the decades. The church is in a state of undress; its octagon has been violently disrobed of its plaster. The nudity of its interior inspires tenderness in me. I wonder if it would be possible to restore it without veiling the defenseless crumbling stone and exposed wooden beams.

I am averse to things that are too neat, which endears Narva to me. Youngsters sit around on a forlorn park bench, bottles of vodka planted in the soil. I hope that, like their grandfathers, they dream of the moon and not of Lamborghinis.

Carried by a little elevator to the top floor of the church tower, we gaze out in every direction upon the vast, even landscape. I see industrial infrastructure and uniform apartments shaped like Ls and Vs. I can see Russia from God’s house.

We visit the Narva Castle. Monuments are dull, but here I am arrested by a bronze Lenin whose arm, once leading the workers of the world towards a radiant future, now haplessly reaches for bright blue containers of construction and maintenance materials.

It would have been a better fate to have been forcefully pulled down from his pedestal Such an act at least betrays fear and respect and a long-nurtured desire for retaliation. To be relegated to an obscure corner, out of sight, only reflects irrelevance. A “Funded by the European Union” sign stands there, as if to taunt him.

“RAPID SECURITY” says a panel on the fencing. I think I prefer the slow kind.

Tuesday. A man named Dennis comes and talks about teaching kids to code. He says things like Estonia is a really juicy piece of pie and talks about the attractiveness of the corporate tax regime. Like most entrepreneurial types, his irksome goal-oriented optimism evokes a profound antipathy in me.

Fortunately, he doesn’t stay too long.

I am overjoyed to start walking.

We head straight for the river that Russia has put there to keep us out. A torn landscape of terraces and eroded rocks. Vestiges of the supporting columns of a bombed bridge from the Second World War remain standing a few meters away from the rebuilt viaduct. Everywhere I find plants growing from ruins.

We contemplate the verticality of church spires and cell phone towers, reflective of

successive spiritual and material paradigms of power, but in some ways aspiring towards

the same synoptic supremacy.

Valentina finds two bronze cylinders sticking out of a wall like the barrel of a shotgun.

We enter a labyrinth of garages. Hundreds of numbered red doors, some corroded into involuntary paintings. I think of Rothko. I think of those game shows where the victims-contestants have to choose one out of several options to obtain either a brand-new car or a lifelong regret. I think of the miniature universes behind these gates: equipment, contraband, furniture without memories.

When I say labyrinth, I mean it. To find our way out, we have to act like cats: climb roofs,

cross a barbed wire fence. Some of us face fears. We rupture our everyday habits of

movement and now we’re fully adrift: this is no longer a leisure activity.

A brief exploration of an abandoned house covered in trilingual graffiti. It is four floors tall and we enter at the top: one might descend the staircase or fall one’s way down into a foggy pasture by the river. A small concrete structure, perhaps an animal residence, beckons me. Do you want to go down there? Aiwen asks me, and her anxious eyes plead with me to say no.

There are other things to discover. The floodgates of the river open, and the initially pitiful stream becomes a respectable torrent. We stop for a while to watch the cargo train shipments of chemicals from Russia when my eyes are drawn to a patch of brightly colored potted flowers bordering the shrubbery. Upon closer inspection, we find the flowers are made of plastic.

My heart is stirred by such a tender intervention in this otherwise unkempt and neglected

corner of Narva. I want to sit very still for a while and allow myself to feel things, but people are chatting. Someone produces the lackluster suggestion that the flowers must mark the grave of someone’s pet and I am briefly overcome with loneliness.

At an observation point by a rusty dog park, overlooking the powerplant, we meet another

Dennis – a local drunk who exudes a pungent alcoholic aroma and is exceedingly happy to have found some people to talk to, even if none of them share his language. He asks us our names and where we are from, on multiple occasions. His English is limited to For example, which becomes his mantra.

Caspar and I laugh at the emerging dualities. Two castles: the well-maintained attraction of Estonia, the old and crumbling ruin of Russia. Two Dennises: the innovative optimist in Estonia, the boisterous eccentric in Russia. It’s perfectly clear on which side I grew up, but more and more I find myself wishing for a visa.

Victory Day, or:

A man in a blue shirt approaches us, jubilantly shaking our hands. He repeats something we don’t understand. He writes with his finger in my palm: 1941 – 1945.

I think to myself he got the dates wrong. Then I remind myself It isn’t my war.

I remind myself

That ten million Soviet soldiers perished,

ten times the Americans and British combined.

I remind myself

of seventeen million Soviet civilians

and I try to imagine every human being in my country

and everyone I know

hung from trees on both sides of the road

buried anonymously in mass graves

and forgotten.

In France and Germany, a plurality of respondents believe the Americans contributed most to Europe’s liberation.

A man in a blue shirt approaches us, jubilantly shaking our hands. He repeats something we don’t understand. He writes with his finger in my palm: 1941 – 1945.

I think to myself he got the dates wrong. Then I remind myself It isn’t my war.

I remind myself

That ten million Soviet soldiers perished,

ten times the Americans and British combined.

I remind myself

of seventeen million Soviet civilians

and I try to imagine every human being in my country

and everyone I know

hung from trees on both sides of the road

buried anonymously in mass graves

and forgotten.

In France and Germany, a plurality of respondents believe the Americans contributed most to Europe’s liberation.

The English, global leaders in the self-delusion industry, believe they themselves did.

But it’s common knowledge that the Russians distort history.

I complain that my knee hurts. I remind myself of trenches.

I complain about construction workers in our room. I complain about dust in our room.

I remind myself that when the dust had settled on this city, out of every hundred buildings there were two left standing.

Let’s eat with the locals, Caspar says.

We walk to the canteen.

It doesn’t look very fresh.

We walk to the other canteen.

There are only dead animals to eat.

We walk back to the residency and the pea soup is nearly finished.

I complain about being hungry,

then I remind myself that I’m not.

I remind myself that I’m happy

But I can’t seem to remember anything.

The Town To Be Refreshed

Death is virtual reality.

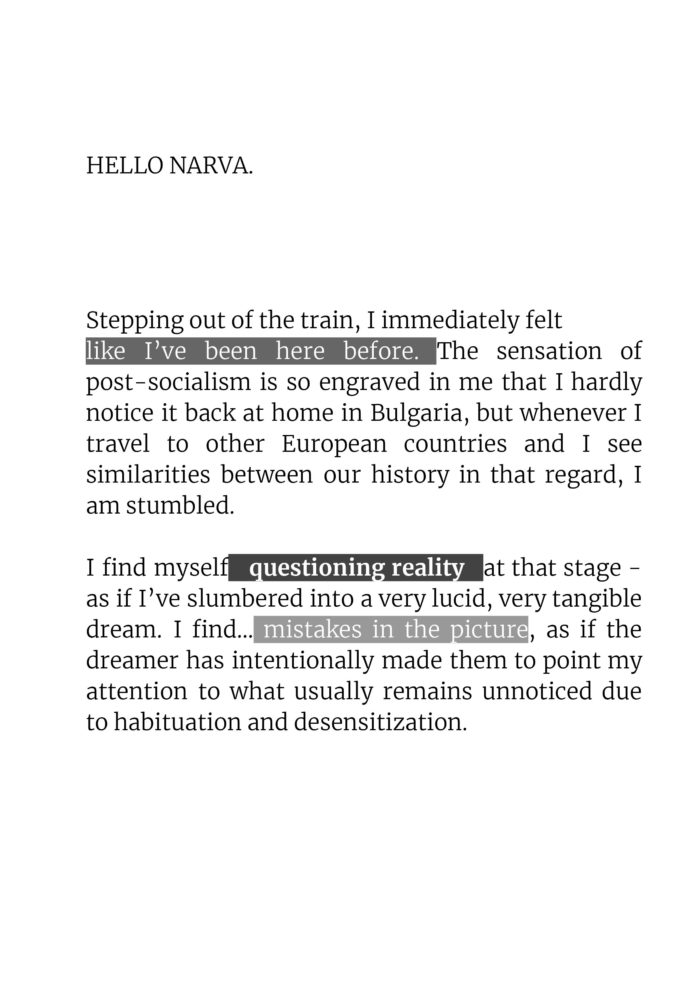

I keep thinking about this line during these days in Narva. The Estonian town at the convergence of Russia and Finland borders, turns out to have a major population of war widows. Wherever I go, there are cemeteries, flowers and crosses grow out from the mottled urban fabric, telling the city’s rich history that I haven’t fully grasped yet.

I thought about our conversation about your parents, who have walked out of time. You said it’s odd to feel that the world is running as normal, including your own everyday life, while your history of being someone’s hope towards the future has come to an end. You are now, officially, facing death with your bare hands. I wish I could hold your hands, but we were merely pixels on each other’s screen. Instead, I carried on with the weight of that silence between us, even after you walked out of my time.

Timeline, multilayered space, burnout, loneliness, the user, the institution, the blockchain. All these topics I have been busy with lately, whisked away at the moment I arrived Narva. The extraordinary spatiality, the prominence of old trees and decaying architecture, the thin trace of urban activities, they all seem to have their own spacetime. They are there, neither specifically welcoming to my human presence, nor do they rejecting. My human narrative is only, merely, one of the many. This is the perfect place to retreat while still having some basics of civilizations. I said so to Tommi and Kaisa, the organizers who invited me to this place. They smiled and agreed.

Estonia is famous for its advanced digital infrastructure, and Narva is not exempt from the national benefits. However, people here don’t seem to be crazy about it at all. In fact, I hardly see pedestrians walking with their smartphones. I wonder if it’s because of the small scale of the city, or its senior population, or the lack of prominent economic actors. Maybe all of these. I find it refreshing to have such a calm relationship with the communicative economy, but the young people we’ve met seem to find it depressing. “Narva wants to be the next European culture capital”, one says. “More young people will come to Narva soon”, another promises. “Narva will be refreshed”, the third chimes. I had never thought of digital technology as a tool of gentrification before, but now I realize it always has been one.

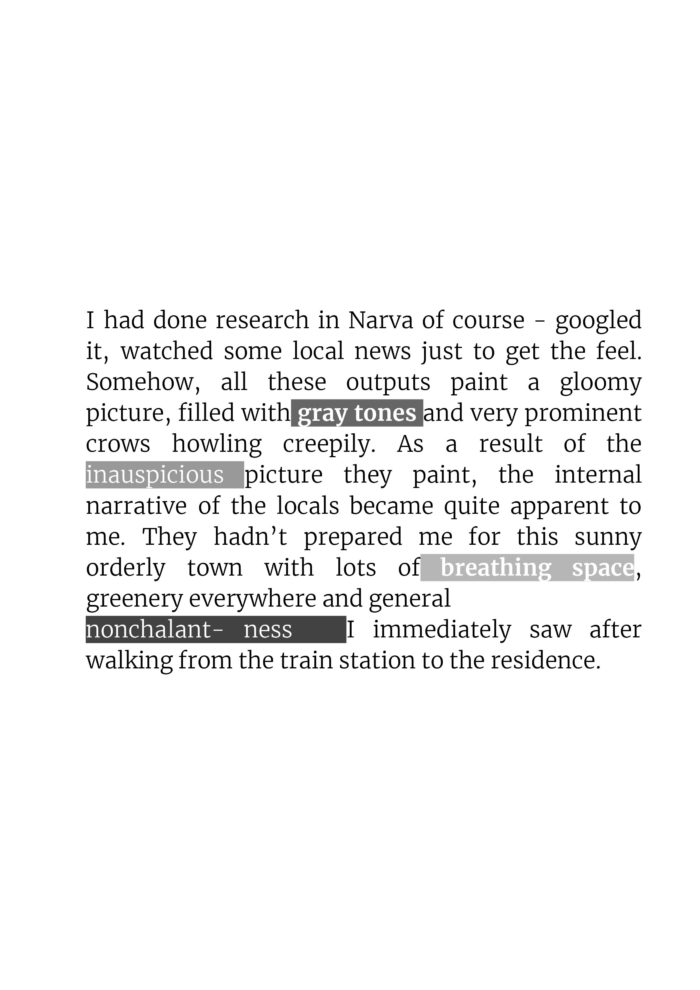

As a depressed techno-optimist, I asked, is there any plan to integrate the original population here? I meant the senior population, the war widows who still live in their trauma and are not catching up with the world. The question was diverted and left unanswered. I do understand that. Unlike me, they have a stake in the situation. The town’s (dis)integration of contemporary urban culture matters to their career, their family, and their future. I am just a foreigner who can relate to this town as a digital resort for my own, at best.

In my previous life, when China was post everything and not being anything, I remember the national anxiety to prove our relevance to the world and to ourselves. China has a long history, but we are not old. We have so much to offer, why can’t the world see that. We can speak the same language as you request, we can prove that we have civilizations as you demand. Five-thousand-year of history is a burden, we need to catch up, faster and faster. You said that is all silly, I said you are too privileged to understand.

Do you remember the book we read together? The female Peter Pan finally confesses to her lover the reason she has been refusing intimacy. “I have old people smell”, she quivers. I can’t remember how her lover responds, can you? You know my grandma has been persistently not dead, but also not alive. The family group has been sharing distressful articles about the life of being old. Everyone is terrified. The dread of no longer having agency, the aversion of being a drag and the fear of being abandoned mix all together. My grandma no longer understands any of these, luckily. Otherwise, she wouldn’t been able to bear to see her children like this. Death is, after all, only a virtual reality. It merely exists in the imagination of the alive.

When I took off the goggles, I was inside a taxi that is running towards the lighthouse, where the borders crossed. Our taxi driver doesn’t speak English, but her audio player is full of English-speaking pop songs. At the moment she stopped in front of a wild beach, her audio was playing “Forever Young”. The song stayed in my head for a while, as we were standing on the beach enjoying the breeze. I thought there is something refreshing about forgetting the old, while the whole world is worried about aging. Narva is like the city version of Benjamin Button, born old, grow younger. I heard it’s also one of the few that haven’t affected by climate change, yet. It seems to be a resort of everything, at least for a while.

Some are like water, some are like the heat

Some are a melody and some are the beat

Sooner or later they all will be gone

Why don’t they stay young?

It’s so hard to get old without a cause

I don’t want to perish like a fading horse

Youth’s like diamonds in the sun,

And diamonds are forever

Forever young

I want to be forever young

Do you really want to live forever

Forever, and ever?

MetaNAR

Spring School 2019

→ Весенняя Школа 2019

→ Kevadkool 2019

→ Kevätkoulu 2019

MetaNAR

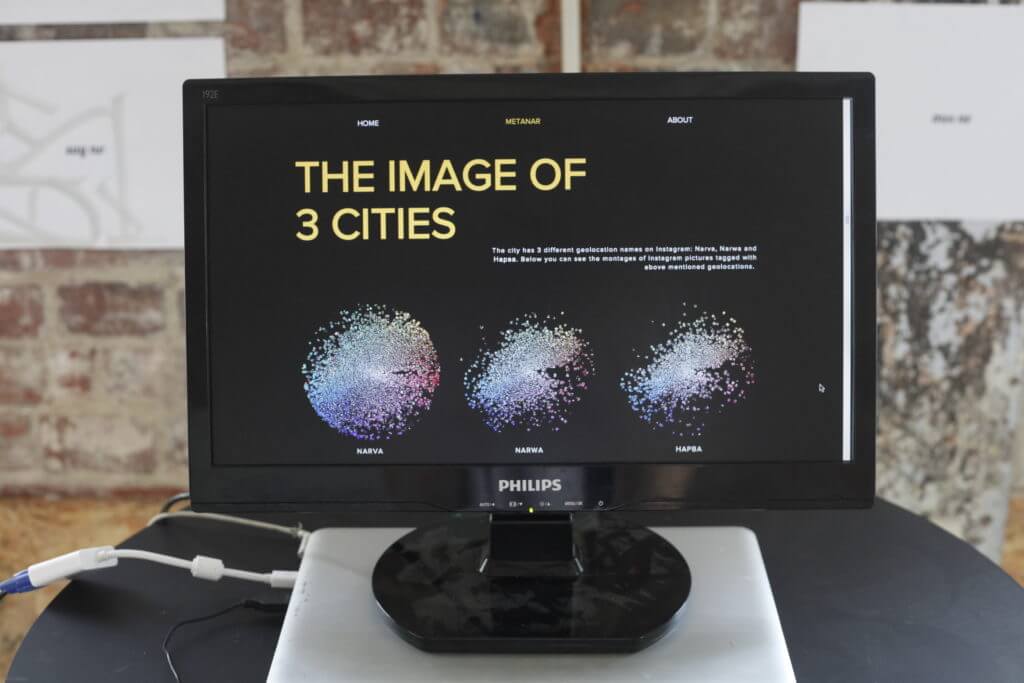

In the metaNAR – Narration for Digital Society Workshop led by Damiano Cerrone, five participants used digital means to explore the metamorphology of Narva, process the digital footprint and map the collective landscape of the city.

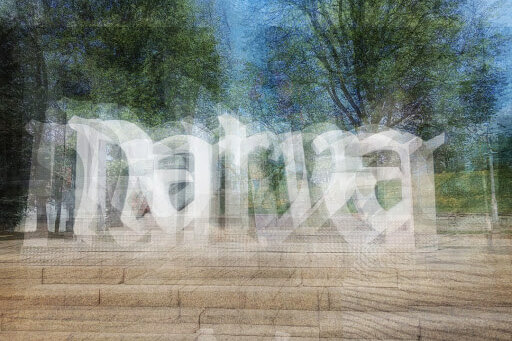

MetaMorphological research explores the speculative form of the city by examining the shape of the urban environment and its cultural landscape, emphasizing the significance of technology and the rules of media platforms for the creation of urban loci. metaNAR was an attempt to apply this framework to the border city of Narva, where we introduced a new, synthetic landscape.

We leveraged GANs and style extraction (neural style transfer without the content loss, in collaboration with Rheza Budiono) to encourage discussion and broaden speculation about the condition and future of a city, about the way in which its complexities might unravel. Through experimenting with these technologies in Narva’s post-industrial landscape, we eventually arrived at a place of hope: that computer vision, large-scale image analysis, and cartography, when coalesced, can be tools for abstracting the shapes and functions of a city, unleashing the collective imagination of groups, giving them the capacity to redefine their own environment.

We are proposing to write an article about the use of new digital media as tools for reconfiguring the imagination of contemporary cities.

Deconstructed Field Study

Spring School 2019

→ Весенняя Школа 2019

→ Kevadkool 2019

→ Kevätkoulu 2019

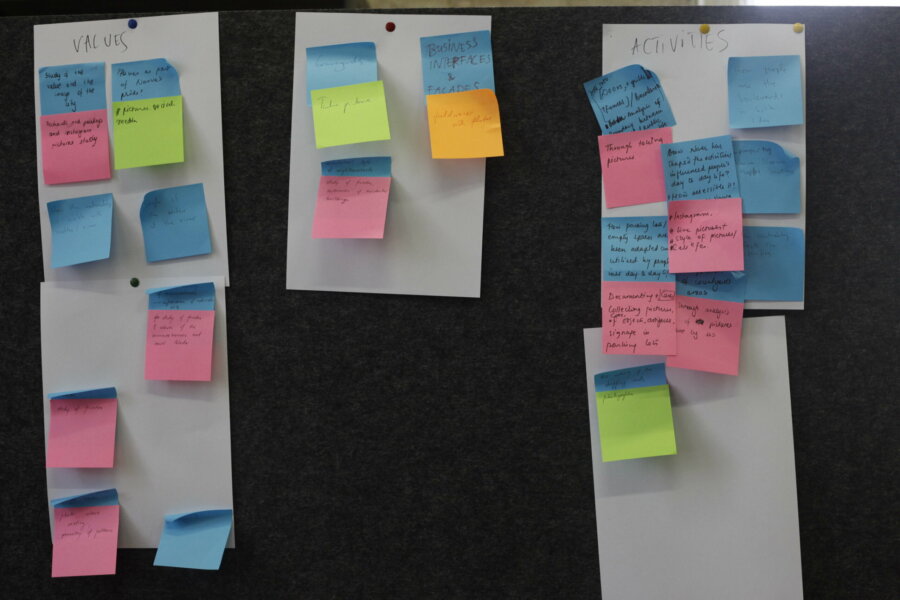

In the Deconstructed Field Studies -workshop lead by Polina Medvedeva, participants interacted with the city and its inhabitants documenting small stories and local knowledge about the informal economies and non-conformist communal structures of Narva.

In 2012 Narva’s old town gets a brand new building, standing next to the Town Hall. Freshly inaugurated Narva College, say Kavakava Architects, reflects the former Stock Exchange Building destroyed during the Second World War. Yet for some Narva older residents, the modern architecture comes as a challenge to their representations.

When entering the building shaped with clear wood structures, a sense of utopia invades the thoughts. A new generation is busy going in and out through the glass doors, discussing at the fancy café or leaning over Estonian and Russian books in the cosy library. Somehow, accounts of the former Kreenholm factory’s social life come to mind. Perhaps, the youth has found its new headquarters.

Among these ambitious youngsters, some have crossed the border from neighbouring Russia. The hybrid situation of Narva appears as an unforeseen opportunity for those who aspire to open the door to Europe.

And yet… just like the golden age of Kreenholm don’t include hard work, stress and health problems in the picture… is the European university utopia resisting the reality of Narva’s complexity? How is this new generation of Russian-speakers arriving in Narva going to face Estonia’s conflicted past? How are Estonians going to process the changing structure and ambitions of the Russian-speaking population? How is the identity of Narva going to be transformed?

As the medieval castle stands still on the bank of the undisturbed Narva river, it feels hard to find the clue, and so we wonder… What will be the face of the future Narva?

Spring School Mentors

→ Весенняя Школа

→ Kevadkool

→ Kevätkoulun mentorit

POLINA MEDVEDEVA is a Russian-Dutch filmmaker and artist based in Amsterdam. Her work researches the notion of informality, focusing on informal economies and non-conformist communal structures, their principles of which influence the aesthetics of her videos.